She's Back on Broadway!

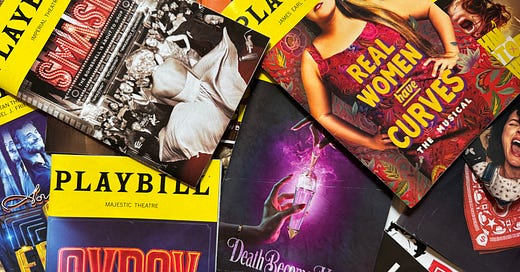

Thoughts on writing about theater after a long drought, and what I saw in the 2024-2025 season...

A bunch of years ago, I ran a Broadway blog called The Craptacular with my friend and partner in shenanigans Aileen McKenna. It was a trip. We interviewed the big stars. We got a shoutout on NPR and were featured in the New York Times. We went to the Tonys. We did the parties and the opening nights. We experienced the whole damn thing, for the better part of a decade. And it was fabulous.

And then we burnt out. Well, I did anyway.

It was hard to run a blog that effectively operated as a second full-time job because, unlike my first full-time job, it paid almost nothing. But I also found it difficult – and exhausting – to navigate Broadway’s many political complexities. The producers who blackballed us when we ran stories that didn’t suit their agendas. The people in the “mainstream” theater press who saw us as interlopers. The vows of silence and complicity that you need to uphold to work in a small, interconnected ecosystem like Broadway when whole shows can be made and broken, and millions can be gained and lost, through word-of-mouth.

Of course, for every entity that perpetuated all these experiences, there were ones that always supported us and had our backs. But by the time I was turning 35 – incidentally, the same year that Hamilton opened on Broadway – I was done. I was so done that I didn’t just stop writing about theater. I also mostly stopped going to the theater.

That changed this year. The simplest explanation I can offer is that I missed it.

I was a theater kid. I didn’t just perform in musicals like Hello Dolly! and The Sound of Music when I was in high school. I followed actors and chased down obscure scores. All of my babysitting money went toward tickets to whatever national tour was in town. I had opinions about shows I’d never seen based solely on their cast recordings. I wasn’t even a theater major at Emerson College, but the kids who were would drop by my room to talk about John Cameron Mitchell or Jason Robert Brown. I was madly, deeply in love. And I forgot about that for a while.

The first show I saw this season was Swept Away – a musical about a shipwreck with songs by The Avett Brothers. There was swashbuckling. There were handsome men. There was John Gallagher, Jr. looking like a bearded hobo. There was cannibalism.

I knew before the lights even went down that I was so back.

The irony here, of course, is that Swept Away was the flop of the season and perhaps, the most high-profile musical flop of the decade so far. I loved every single minute of every gory, fucked up, confusingly Christian minute of it. It reminded me that I loved the theater, and especially musicals, but it also brought something back to me that I had not really considered since I was churning out thousands of words a week for The Craptacular.

I didn’t just love theater. I also loved thinking and writing about theater, especially when that thinking was focused on a show that was as contested and fleeting as Swept Away.

It’s too late to talk about this season. It’s done. The Tonys were last Sunday. But here I am, trying to find my way back to this piece of my own heart. There’s no timeline on that, right? I hope you enjoy.

And yes, there are a few more of these to come.

Dead Outlaw

A lot of musicals this season were about dead people. The one in question here is Elmer McCurdy, a real-life, mostly unsuccessful mid-tier criminal whose dead body somehow experienced more of the world than his living one ever did. Elmer is played by Andrew Durand, who spends more than half the show as a disturbingly realistic corpse. To me, this was just the beginning of this show’s… uh… charms?

I’m not sure anyone right now is putting contemporary music on a Broadway stage in a more credible way than David Yazbek. So much theater music is Rodgers and Hammerstein pastiche or decaf Jonathan Larson. It is often hazily reminiscent of a theatrical someplace-else. Yazbek’s songs feel drawn from actual rock music (with sides of jazz, klezmer, surf rock, and murder ballads), and not just a musical that’s going through rock’s performative motions. This feels especially unique because Dead Outlaw is absolutely not a rock opera. Unlike that sticky, much-maligned format, Dead Outlaw has a real book (by Itamar Moses) and it’s a subtle one – quiet, neatly paced, rumbling underneath with McCurdy’s sense of pain and failure. That subtlety is what gives the songs their outrageous kick. They are loud, ear-wormy, sung straight to the audience, and played by an onstage band that looks and sounds like the kind you’d imagine would exist at a roadside honky tonk, even though some theatrical magic is of course in play here.

This concert-style sensibility, and the unrelentingly dark subject matter, reminded me of another weird-as-hell musical I loved – Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, which imagined its presidential protagonist as the lead singer of an early aughts emo band. That show opened and closed quickly. In 2010, Broadway and the world did not seem quite ready for a comedic satire about a populist, proto-fascist American president whose defining legacy was a genocide. Watching Dead Outlaw, I wondered if Broadway has both toughened up and lightened up a little bit. Or maybe we have simply gone through so much as a society since then that we can now see ourselves more clearly in darkness.

Floyd Collins

Here’s another dead guy. Floyd Collins, also based on a true story, tells of a man who discovered a cave near what is now Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky. Unfortunately for him, he got stuck down there under collapsing rocks and died. Fortunately for us, composer Adam Guettel – who is Richard Rodgers’s grandson, casually – saw this as fit material for a musical.

It premiered off-Broadway in 1996 – exactly two weeks after Rent opened at New York Theater Workshop – and only ran for 25 performances. But Floyd Collins was heard like a kind of thunderclap across the theater world. Jonathan Larson was dead. Guettel was a new and fascinating prince, and he had the pedigree, and the astonishing sense of melody and lyricism, to prove it.

All of this seems neatly forgotten with this production, I’m not quite sure why. But many critics, and indeed the show’s own producers, seem to have lost the (literal) plot – and the history – that comes with this show. Despite these songs being taught in MFA programs, despite their presence in countless cabarets, despite existing in the public consciousness long enough to go viral, Floyd Collins arrived on Broadway for the first time ever without particular fanfare, with phoned-in Playbill art, and without so much as a souvenir program on sale in the lobby. Quoth a million Xennial theater nerds, “What the fuck?”

I was also frustrated that some critics seemed to zero in on the show’s decidedly unorthodox structure and its lack of focus on Floyd as a character. I don’t get their quibbles. Both make sense if you consider the spirit in which they were written. Guettel was 29 when the show premiered, and was pushing hard on traditional musical form with Floyd Collins, trying to bend it as far as he could without breaking it. Arguably, he actually did, but how many others were even trying?

The ensemble opens the show, but then it quickly recedes and Floyd is left alone onstage for the next twenty minutes, singing into the open air of his newly discovered cave, his echoing voice his only company. I still love the poignancy of these scenes, the metaphor of Floyd, ecstatic with song, embarking on his quest into the unknown – a thing only he can do, because only he understands it.

Guettel was clearly reaching for something specific here – a thing that I’ve always thought was linked to his grandfather’s legacy. Richard Rodgers wrote the most beautiful, powerful, and complex song for a man to sing in any musical, ever, in his “Soliloquy,” which closes the first act of Carousel. The opening of Floyd Collins is Guettel’s “Soliloquy,” but he puts it at the beginning, as a way to show the audience that Floyd, the son of hard-scrapple farmers, lives for a bigger dream. Its early fulfillment in the show spells immediate trouble. I’m not sure what critics were expecting when they couldn’t see this form, in and of itself, contained so much of who Floyd is. This is not a bio musical. Princess Diana is not going to sing you a song about her dress. It’s a broad, many-armed, mostly-tragic allegory of the American dream and how it leaves many of us… simply stuck.

This production had its fans – Jeremy Jordan, who is quite possibly the best singer on Broadway right now, was universally well received. The show’s Tony nominations affirmed, too, that Floyd Collins is not an insignificant work. But it won none of them, and the show is closing soon. It feels like shoddy treatment for a show that, in its moment of inception, let us dream big dreams.

I’m so happy you’re writing about Broadway again

Yessssssssss